Clean Architecture - Understand the diagram once and for all

Clean Architecture is a foundational book for software engineers. Once you understand its principles, software design becomes much easier, and you can focus on what really matters.

There is always more to learn about design and architecture. But the book gives you solid foundations of how good software should be built.

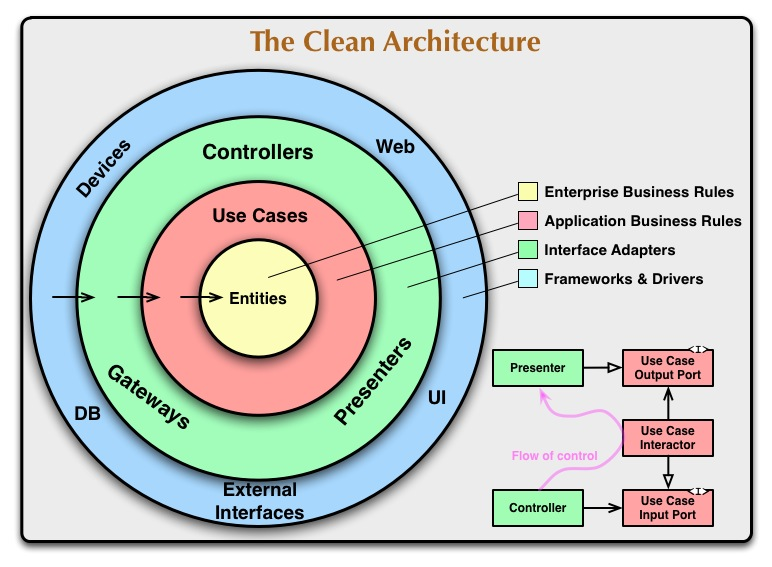

Yet, despite its popularity, I’ve noticed that many developers struggle with the famous “circles diagram.” And I can get it.

So in this post, I’m going to explain the same ideas, but with a different approach, so you can finally get it.

Start with the real problem your software solves

Recently, I built an app called PNLParse for traders.

When you trade, you buy and sell assets. If you sell higher than you bought, you make a profit. If you sell lower, you take a loss. The real calculations are more complex than that, but that’s the idea.

PNLParse takes a list of transactions as input, performs calculations, and produces insights about your trading performance.

Today, PNLParse is a desktop application with a database, a nice UI, file uploads, and more.

But the first version was just a simple Rust script that processed hardcoded transactions.

Just pure logic solving a real problem. At that moment, the software was nothing but the core business logic.

That’s exactly what the yellow circle represents in the Clean Architecture diagram.

Think “Domain” rather than “Entities”

In Clean Architecture, the innermost circle is labeled Entities, but I find that name confusing.

A better and more common term is Domain.

The domain is the problem space your software is built to solve.

For PNLParse, the domain is not databases, authentication, or transactions file parsing.

The domain is: trading performance analysis.

That is why the software exists.

The domain is more than just entities like Transaction. It also includes the business logic, the calculations, the invariants, etc ..

For example:

- recording trades

- maintaining an inventory of owned assets

- calculating profit and loss

- computing performance metrics

That logic belongs in the domain.

Everything else exists to serve the domain

Once you have a clear domain, everything else exists just to make it usable in the real world.

For example:

- You don’t want transactions to be hardcoded → you need file uploads or an API

- You don’t want results printed in a terminal → you need a UI or a HTTP response

- You don’t want to recompute everything every time → you need a database

- You need authentication so users don’t see each other’s data

- You might need billing if you want to monetize your app

None of this is your core business problem.

It’s all necessary, but it is not the reason your software exists.

This is what the outer circles in the diagram represent. They support the domain, they don’t define it.

What users actually interact with: Use Cases

Users never directly interact with your domain. They interact with use cases.

Think of your domain like the engine and mechanics of a car.

The user doesn’t want to understand how the engine works or get their hands dirt. They just want to sit in a comfortable seat, grab the steering wheel, press the pedals, and turn on the radio.

That’s exactly what use cases are.

They provide a user-friendly way to interact with the system.

Examples of use cases might be:

- Upload transactions file

- Get portfolio performance

- Get trade details

Login and registration are also use cases. Even though they are not part of your core business domain, they are still things your application must do.

In Clean Architecture, this layer is often called Application Layer and use cases are defined in the layer.

The job of the Application layer is mostly orchestration between:

- the domain (business logic)

- technical components (database, files, APIs)

- application rules (auth, permissions, billing)

For example, in PNLParse, there is a use case to upload transactions file.

This use case does several things:

- It receives a file from the user

- It extracts transactions from that file

- It sends those transactions to the domain for calculations

- It saves the results in the database

The use case is not doing heavy business logic itself. It’s coordinating different parts of the system. That’s exactly what the Application layer is supposed to do.

The application layer is not technical, It depends on abstractions

Let’s take data storage as a concrete example.

The domain layer does not care about storage and databases. It simply takes some input entities, applies business rules, and produces new entities as output. Whether those results are stored in PostgreSQL, a JSON file, or in memory is irrelevant to the business logic.

The application layer does care about persistence. It needs to ensure data is available for other use cases.

But the application layer must remain non-technical. It should not depend directly on PostgreSQL, MongoDB, or any concrete database technology.

So it defines a contract (interface), describing what it needs.

To persist business entities, the application layer typically defines an interface for a Repository.

This interface lives in the application layer.

Now comes the green layer, labeled Interface Adapters, but often called Infrastructure.

This layer will provide one or different implementations of that interface.

Application layer can then use an implementation of this interface without knowing which one it actually is. At startup (app bootstrap), you can decide which implementation to inject.

Use cases don’t change, and domain doesn’t change.

Use cases as generic entry points

You can think of use cases as technology-agnostic entry points into your application.

They describe what your application can do, not how it is exposed to the user.

In a web application, you typically have an HTTP server.

Each API route corresponds to a handler (or controller) in the infrastructure layer.

A typical flow looks like this:

- The controller receives an HTTP request

- It extracts parameters from the body or URL

- It calls the appropriate use case

- It formats and returns an HTTP response

Everything HTTP related is purely technical, so it belongs in the infrastructure layer.

The controller does not contain business logic, it just adapts the outside world (HTTP) to your application.

Now imagine that tomorrow you decide you don’t want a web app anymore, but a desktop app.

With Clean Architecture, this is easy.

You do not change your domain or use cases. You can even keep the HTTP server code.

You simply add the handlers for the desktop app framework calling your use cases. Llike Tauri commands if you build a desktop app in Rust.

Only the infrastructure changes.

About the blue layer

In the diagram, there is a separate blue layer outside the green one.

Personally, I find this confusing.

Conceptually, it is still part of infrastructure. You can merge both in your head and just think about infrastructure layer in mind instead. Result will be the same, and it’s much simpler to conceptualise.

Inner circles, outer circles, and arrows

The domain is in the center.

There is *no arrow going out of it because it depends on nothing. It is pure business logic and technology agnostic.

The application layer depends on the domain, which is why the arrow points from application to domain.

Application orchestrates domain logic, but it does not influence it.

Application is also not technical. Instead, it defines what it needs. It does this using interfaces.

The Infrastructure layer implements these interfaces. That is why the arrow goes from Infrastructure to Application.

This rule is often violated, which leads to problems such as: using database models as domain entities and coupling business logic to PostgreSQL or an ORM.

Dependency direction with the Repository example

-

Domain defines the business entity

Transaction. -

Application defines a repository interface,

TransactionRepository, usingTransaction, describing the storage needs forTransaction.The method signatures must contain nothing technical.

If the repository can return an error, it must be an abstract error defined in the application layer, not an error from a specific database or library.

-

Infrastructure provides concrete implementations, such as

PostgresTransactionRepository.

Practical usage

A common practice is to create these 3 folders in your project: application, domain and infrastructure. This is not a requirement, but it can helps to visualize the layers.

Where to put things

Now you’re in your IDE with these 3 folders. How do you decide where code belongs?

1 — Is this part of the core problem I’m solving?

Imagine your app as a simple script. No database, no API, no users, no billing, no UI.

If it still makes sense in that context, it probably belongs in domain.

2 — Is this purely technical and replaceable?

If you could change it tomorrow without affecting your users or your domain, then it’s infrastructure.

- SQL or NoSQL queries

- the HTTP framework you use

- cloud providers

- external APIs for market data

- reading from an FTP server instead of an API

These are implementation details. You should be able to swap them without touching your core logic.

3 — If it’s neither of the above

Then it’s likely application layer.

Should you use this architecture everywhere?

No.

The full domain/application/infrastructure separation is a great architecture, but it’s not always worth the cost.

On a small project, it can be overkill. You might end up with more boilerplate code than useful code.

On a legacy codebase, migrating everything to Clean Architecture can be extremely expensive, and in most cases there is little or no business benefit to refactoring 100% of the system.

That said, even if you don’t apply it strictly, it’s still essential to understand these ideas as a software engineer.

If you keep these principles in mind, you can already get most of the benefits by:

- protecting your domain

- avoiding technical leakage into business logic

- depending on abstractions instead of concrete tools.

Also, some parts of your system are more critical than others, and those are usually the places where this architecture matters the most.