Advent of Code 2025 Day 10 Explained - Reactor

You can find my Rust implementation on Github.

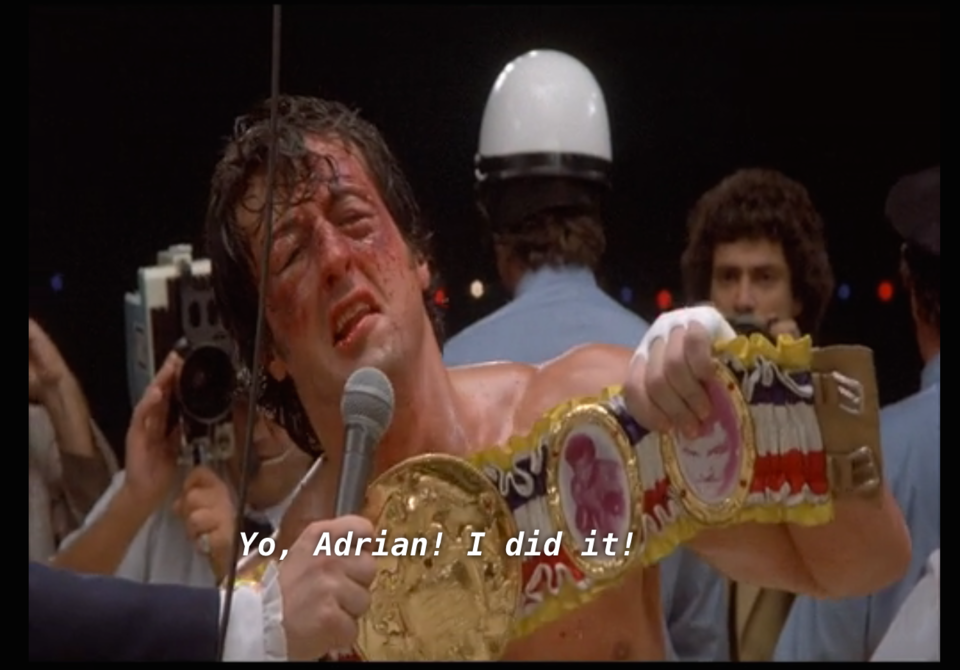

Solving this one feels like:

Part 1

Pressing a button toggles some lights:

- off (0) → on (1)

- on (1) → off (0)

This is exactly the behavior of an XOR.

Our goal is to find the minimum number of buttons to press to reach a given lights configuration.

There are two important things to understand:

-

Pressing the same button an even number of times is equivalent to doing nothing.

Given → is a press:

- With 2 presses: 0 → 1 → 0

- With 4 presses: 1 → 0 → 1 → 0 → 1

- etc.

-

Pressing the same button an odd number of times is equivalent to pressing it once.

Given → is a press:

- With 1 press: 1 → 0

- With 3 presses: 1 → 0 → 1 → 0

- etc.

Which means each button only needs to be pressed at most once. Any additional presses are unnecessary.

Since this is an XOR problem, my idea was to represent everything as bit vectors.

-

[.##.]becomes0110 -

(3) (1,3) (2) (2,3) (0,2) (0,1)become0001,0101,0010,0011,1010,1100

So the problem becomes:

Find the smallest combination of buttons such that the XOR of their bit vectors equals 0110.

Because the number of buttons is small — and each button can only be used once — the number of combinations is limited.

So the solution is simple: generate all possible combinations, compute the XOR for each one, and keep the smallest combination that matches the target.

Part 2

We still want to find the minimum number of button presses, just like in Part 1.

But this time, the joltage keeps increasing. It no longer behaves like an XOR, and that changes everything.

In Part 1, we could press each button at most once.

Now, we might need to press the same button multiple times to reach the target joltage.

Which means the number of combinations can explode, especially given the size of the target joltage in the input.

A first idea to get started

My first idea was to reuse the bitmask representation of buttons from Part 1.

Starting from the target joltage, I tried to work my way back to zero by subtracting “ideal” button presses.

For example, if the target is {3,5,4,7}:

Then the ideal sequence would look like this:

- 3 presses of

1111→{0,2,1,4} - 1 press of

0111→{0,1,0,3} - 1 press of

0101→{0,0,0,2} - 2 presses of

0001→{0,0,0,0}

That’s 7 presses minimum if we had perfect buttons.

But… we don’t. We only have the buttons given in the input, and they’re much less convenient.

That’s the real difficulty: finding the right combination of buttons. With the example input, the correct answer is 10 presses.

But I couldn’t figure out how to systematically find that combination.

So I tried to look at the problem from another angle.

Another way to see the problem

Finding a combination that reaches {3,5,4,7} is equivalent to finding a path from {0,0,0,0} to {3,5,4,7} in a 4D grid, using a fixed set of allowed vectors (the buttons).

The key observation is that the search space isn’t infinite:

- We know the exact target

- We only move in the positive direction

- As soon as we overshoot the target on any axis, that path is invalid

So I tried pathfinding

I implemented a simple BFS.

The idea:

- Start at

{0,0,0,0} - The first reachable states are the vectors corresponding to pressing one button

- From there, keep applying all possible button vectors

- Stop when we reach the target

Something like this:

let mut visited: HashSet<Vec<usize>> = HashSet::new();

let mut current_queue = VecDeque::new();

// start at 0

// first reachable points are the button coordinates

for button in &machine.buttons {

current_queue.push_back((button.clone(), 1));

}

while let Some(state) = current_queue.pop_front() {

// target reached

if *state.0 == machine.joltages {

sum += state.1;

break;

}

for button in &machine.buttons {

let new_v = apply_button(&state.0, button);

if is_in_bounds(&new_v, &machine.joltages) {

if !visited.contains(&new_v) {

current_queue.push_back((new_v.clone(), state.1 + 1));

visited.insert(new_v);

}

}

}

}

It worked for the example input… but completely failed on the real input.

The state space is just way too big.

Can’t find a way to improve it

At this point, I was stuck.

I was convinced this vector-based approach was the way to go, but I couldn’t see how to make it efficient. I even thought there might be some advanced math theorem involved.

I asked ChatGPT for a hint — it told me to look at Integer Linear Programming.

I read a bit about it, but honestly it didn’t feel right:

- Too complex for an AoC problem

- Unrelated to Part 1, and usually Part 1 helps with Part 2

But I still had no idea what to do next.

So I checked Reddit for hints

Most people seemed to be using some kind of magic solver like Z3 in Python. Definitely not the kind of solution I wanted.

Then I found this post.

Super smart, easy to understand, and very much in the AoC spirit.

And actually, it was actually quite close to my first idea.

So I implemented my own version of it in Rust.

Finally, a solution that works

The key insight is this:

If we can reach joltages [1, 2, 3] with n presses, then we can reach [2, 4, 6] with 2n presses.

To reach a target joltage T:

-

Pick a pattern

P(a combination of buttons pressed once, just like Part 1) -

Apply

Ponce → cost is the number of buttons inP -

Remaining target becomes

T - P -

Since the remaining target can be obtained by “doubling” a smaller solution:

→ solve for

(T - P) / 2, then double those presses

We just need to make sure that:

-

P ≤ T(we can’t overshoot the target) -

PandThave the same parity on every position(so

T - Pis even and divisible by 2)

This means we can reuse exactly the same combinations as Part 1, instead of exploring a massive state space like in the BFS approach. With this solution, we don’t generate combinations where buttons appear several times. Instead, we simplify the target.

And it works perfectly.